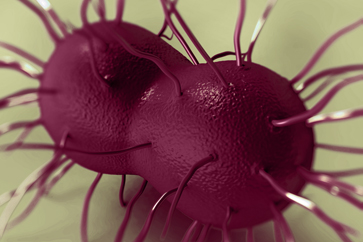

Neisseria gonorrhoeae is one of the most common curable sexually transmitted infections (STI) with an estimated 78 million new gonorrhoea cases worldwide each year [1]. Since the dawn of the antibiotic era, strains of N. gonorrhoeae resistant to guideline-recommended antibiotics have emerged, beginning with penicillin and moving through tetracyclines, spectinomycin, fluoroquinolones and, more recently, treatment failures with macrolides and oral third-generation extended-spectrum cephalosporins [2,3]. Most guidelines now recommend injectable ceftriaxone, sometimes in combination with oral azithromycin [4,5]. However, ceftriaxone-resistant strains have been documented [6-9] and in 2018, the first cases of gonorrhoea with resistance to both ceftriaxone and azithromycin were reported [8,10].

Both gonorrhoea treatment and population exposure to antibiotics select for N. gonorrhoeae resistance [11]. Only surveillance can ensure that clinical guidelines match actual patterns of N. gonorrhoeae antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [12-14]. However, surveillance faces a number of implementation challenges because it relies on bacterial culture of specimens from people with infection. In most low- and middle-income country settings, bacterial culture and nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) to identify infection are not available. For this reason, clinicians treat only symptomatic patients based on identification of easily recognised symptoms and signs and without testing, an approach known as syndromic management [15]. This approach limits surveillance because asymptomatic infection cannot be identified [16]. Clinically, it also results in overconsumption of antibiotics because many of these presentations may be due to another pathogen. In high-income countries, culture-based diagnosis has been largely replaced by NAAT testing, which offers higher sensitivity and facilitates asymptomatic testing, but also reduces the availability of culture isolates for resistance testing and surveillance [17].

Read more...